Last week I spent the evening with Jason Valentine of Thunkerkiss Coffee while he roasted coffee. Jason is a small batch coffee roaster here in Columbus; he roasts out of his garage and distributes his beans to area vendors and restaurants. Even if you don’t know his stuff directly, chances are you’ve had it or seen it around Columbus.

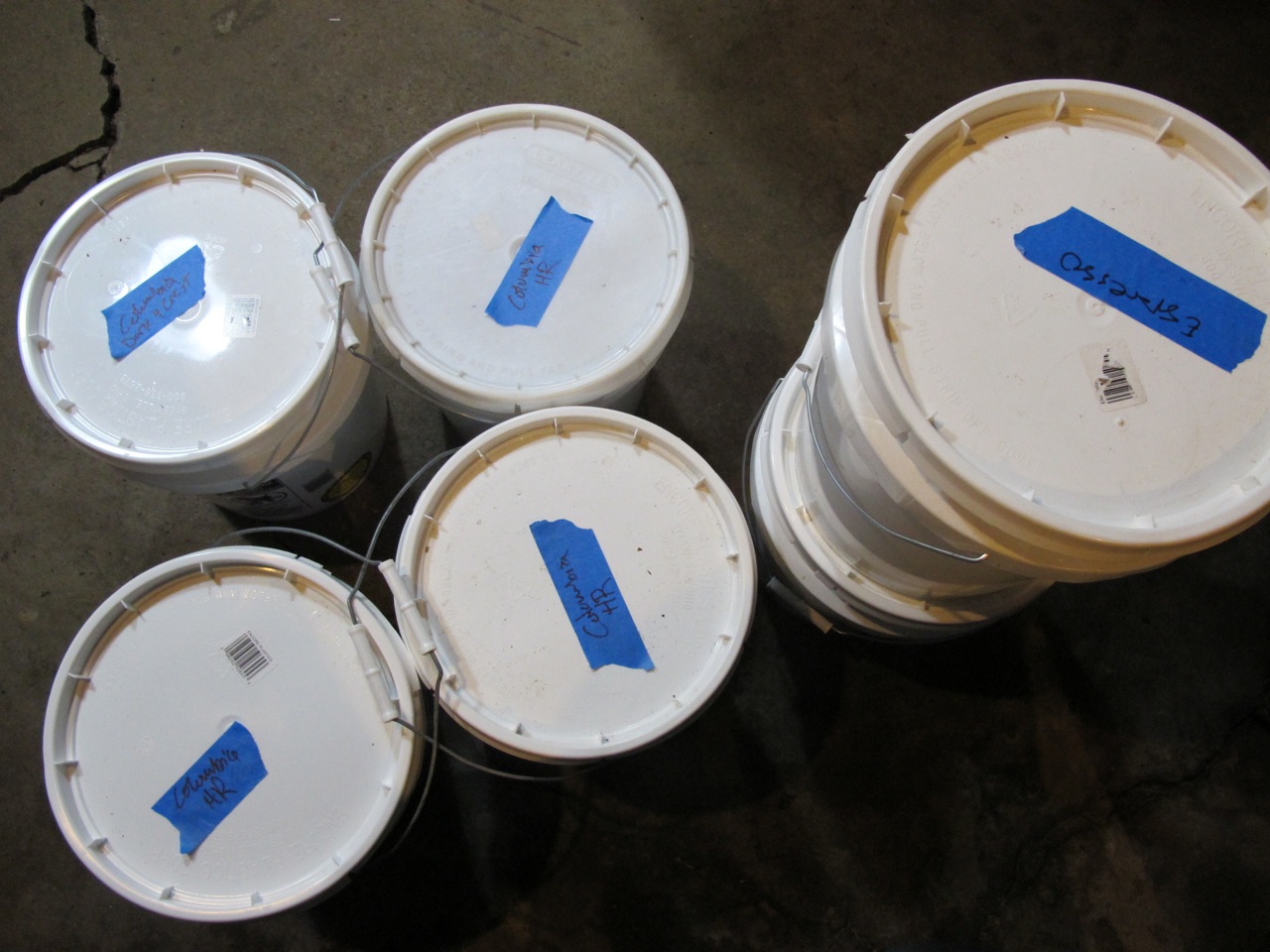

I’ve taken a number of workshops on coffee and coffee roasting, attended tastings, etc., but I’ve never had the chance to just sit and ask endless questions about the roasting process. We began in Jason’s basement, where he stores bags of green coffee beans. He roasts 1-2 nights per week. Before roasting, he weighs and sorts the beans into labeled containers, all based on a spreadsheet listing the customer, the roast(s) they’ve requested, and how they are to be delivered (6 oz bags, 12 oz bags, etc.). Some vendors brew his coffee for their restaurants, some retail bags of whole beans, and some do both.

Jason roasts single origin coffees, meaning they come from one specific place, although he does make some of his own blends, such as the espresso blend. The green beans can be stored for a long time; they are processed out of cherries from the coffee plant. The cherries have been pulped so we’re left with just the internal bean, and sometimes the mucilage, a thin layer surrounding the bean itself. Some Ethiopian beans, for instance, are dried out before de-pulping, which lets the mucilage harden around the bean, adding a certain flavor when roasting. Even before these beans are roasted, you can identify different characteristics just by sticking your nose in the bag.

Roasting takes some time, so we started with a shot of espresso made from his espresso blend.

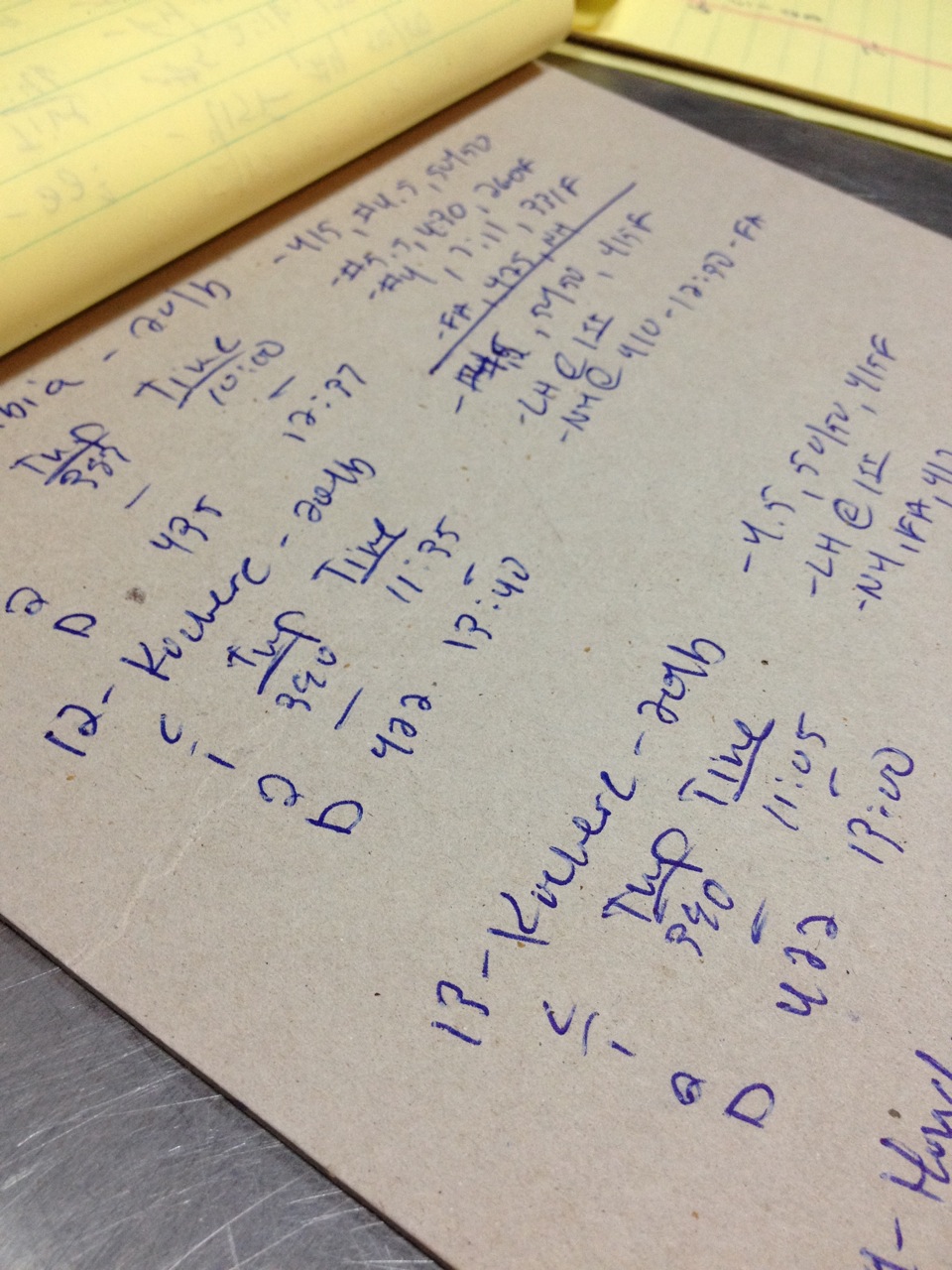

Jason has been roasting for a couple years now. He keeps detailed notes of the timing and temperature from each roast.

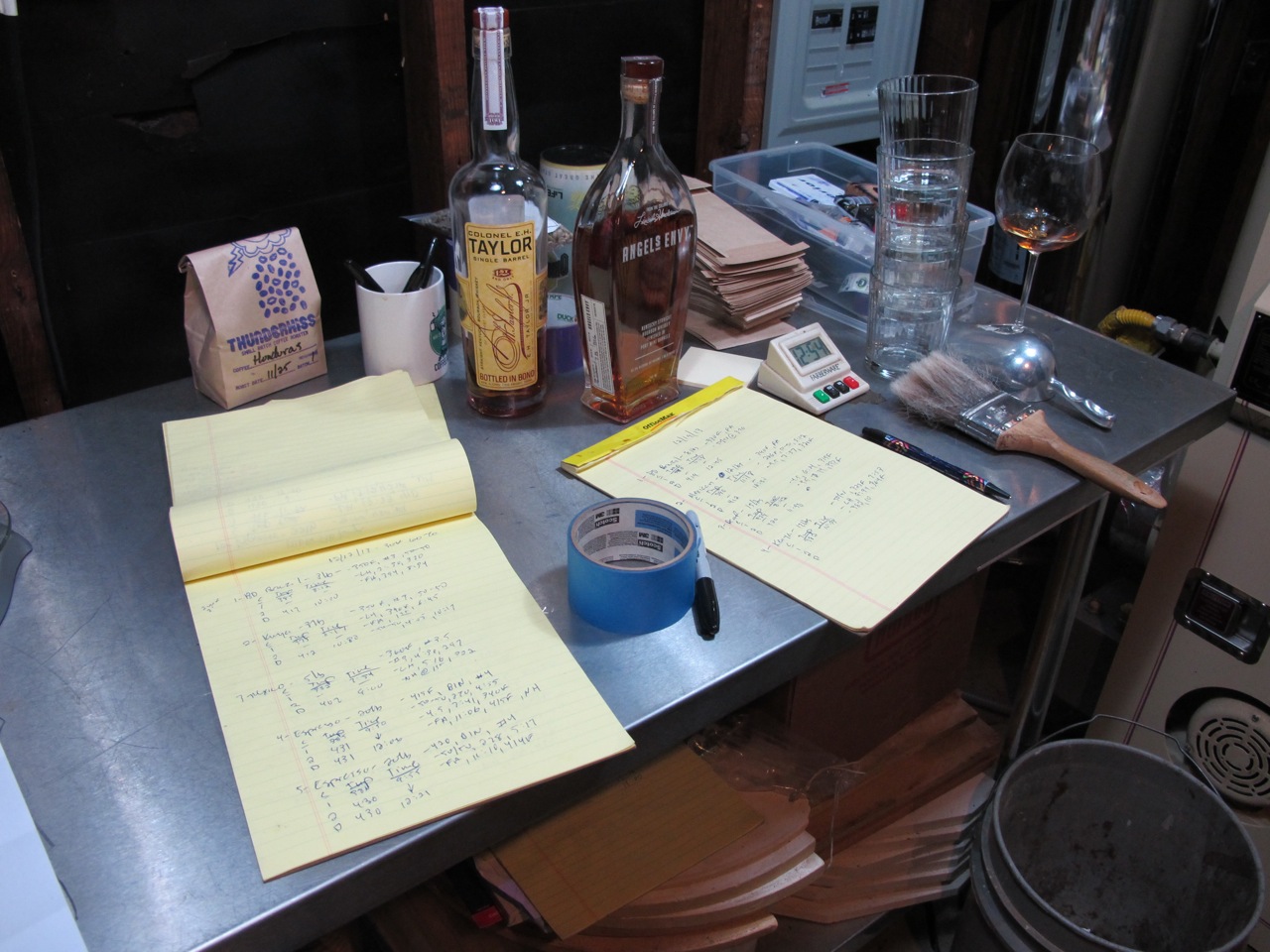

All of the essential supplies.

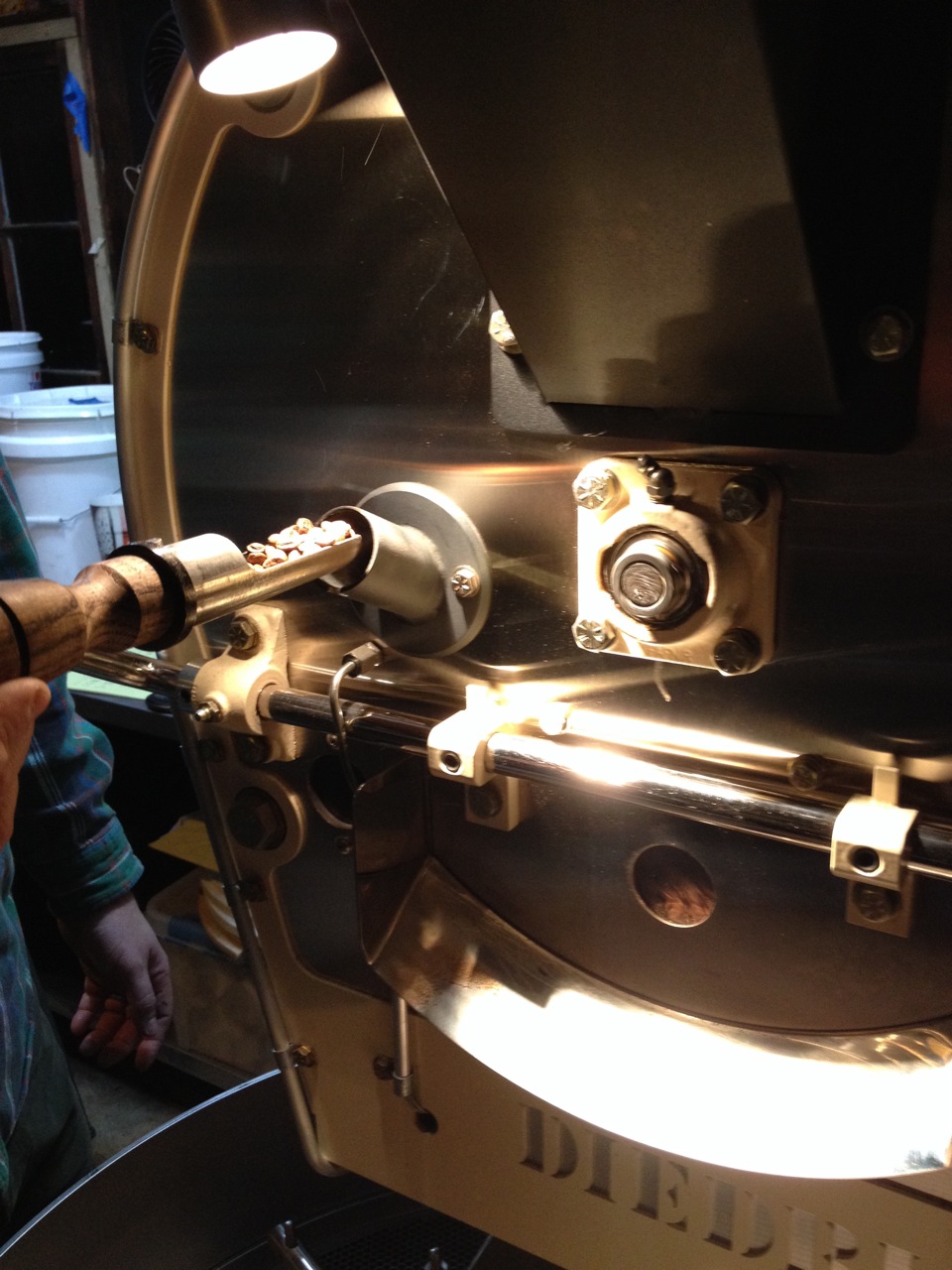

As the roaster is heating up, the green beans are placed in a hopper on top.

Jason roasts on a Diedrich infrared roaster. This type of roaster is compact, more energy efficient, and it uses a radiating heat to roast the beans, rather than a direct flame on the drum.

The entire roasting process takes roughly 20 minutes, depending on the bean, the amount you’re roasting, and the type of roast you’re aiming for. The real factors of roasting include time, temperature, and air flow. The final roast depends on the manipulation of these three elements. While certain beans innately contain different flavor and aroma profiles (some are naturally earthlier, some brighter and fruitier), they can be roasted at different temperatures and for different times to highlight these characteristics.

The first stage of roasting is called the drying out phase. It lasts approximately 4-5 minutes, and heats the beans to the point where the water in them evaporates. Even at this stage, Jason can control how much air is flowing around the beans. Adding more at this point results in a brighter, more acidic roast.

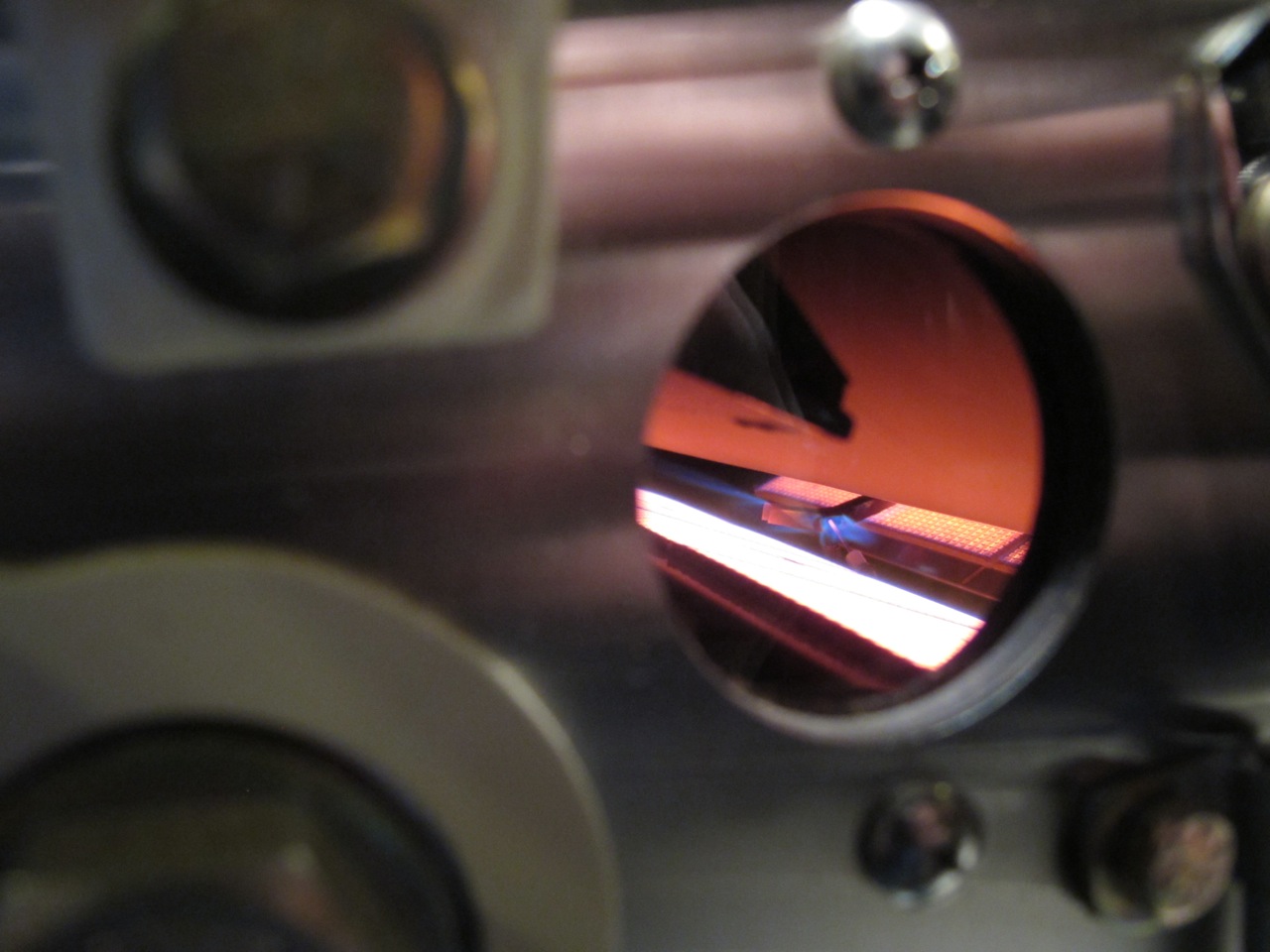

This tool allows Jason to check samples of the beans during roasting. He can examine the color and aroma.

At this point the beans are entering the second phase: the maillard phase, also known as the “cinnamon phase.” This happens around 300 degrees F, and here the color begins to develop. (I learned later that “maillard” refers generally to the browning that happens when food is cooked, like bread or meat.)

Once the cinnamon phase has passed, the roaster is working toward first crack. At this point there’s a literal crack – a whole lot of them, in fact – as the center of the bean is fracturing and the sugar in it melts. It sounds a like tiny little popcorn popping. After this you are headed for second crack, when the sugar crystallizes and burns into carbon, and the beans express oil that can coat them. Most roasts are stopping just short of this point because the burnt sugars lead to more bitterness. Once the roasting is complete, Jason opens the hopper that dumps the hot beans into a lower tray. The darker the roast, the smokier the process, and the more oily the beans will look.

A series of levers in the tray begin swirling the beans around. At this point, Jason shifts the airflow to a fan that draws air down through the beans. This cools the beans and stops them from baking any further. Given the colder temperatures of December, the beans cooled quickly.

At the front center of the tray is a flat plate without any air holes. Once Jason turns off the levers, he brushes the beans off this plate. The plate has heated up after coming into contact with them, so brushing the beans away keeps them from burning.

Once they’re cooled, he can slide the plate open, turn on the mechanism, and the arms sweep every last remaining coffee bean into buckets. While this is happening, the roasting drum is brought to temperature and prepped for the next batch.

The completed roasts are labeled and dated, and ready to be delivered or sorted and sealed into smaller bags.

I very much enjoyed hanging out with Jason. He does incredible work, and his passion for coffee and everything about it shows through his willingness to talk about it and teach it. We’ve been sampling a number of his roasts at home, and have loved every one of them. If you haven’t tried his coffee yet, do so soon. Look up his website (thunderkisscoffee.com) for a list of where to purchase his beans or which restaurants are serving them.